From measuring head length to advanced facial biometrics: The history of criminal identification

How did the police catch villains back in the old days, before the dawn of computers, fancy tech gadgets and automated biometric identification systems?

The way we identify criminals has come a long way throughout history, thanks to advancements in technology and forensic techniques. However, from early techniques of measuring the length of an ear or middle finger, to the present day where advanced biometric technologies can identify a suspect in seconds, the essence of police work has remained the same: focus, patience and persistence.

Bertillon system: Sit, stand, raise your arms… and smile

Imagine you are a police officer in the late 19th century. There was a robbery in a wealthier district of the city, one of a dozen in the last couple of months. This time you were able to catch the main suspect. You handcuff him, put him in a horse-drawn wagon and off you gallop to the police station. But what now? You don’t know who this person is and there are no computers to help you identify them, no searchable databases. The uniqueness of fingerprints has not been discovered yet. What do you do?

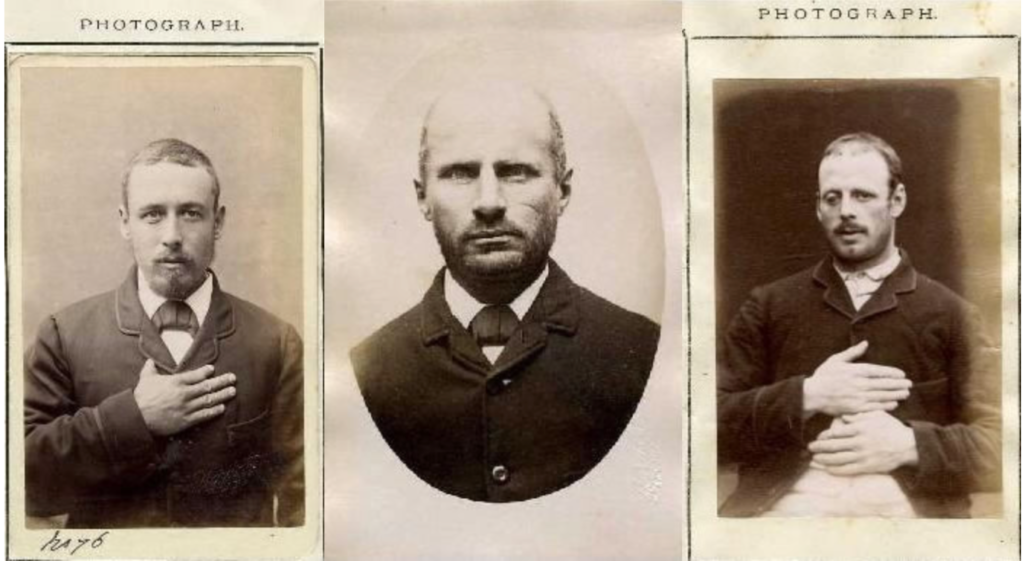

Source: Wiki Commons/Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Howard Gilman Foundation Gift, 2001

You take some precise measurements of the suspect: head length, head breadth, length of middle finger, length of the left foot, and length of the cubit (distance from elbow to tip of the middle finger). You complete the procedure by taking a photograph of them. After all that, you dig deep into the records of all criminals you have at the police station and manually try to find someone with the same measurements. Great work, you just used the Bertillon system.

The French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon invented the system in the late 19th century. He based it on the idea of people having different combinations of lengths and widths of their body parts, which should be measured and used to identify unknown perpetrators and known recidivists.

What exactly did anthropometry measure?

- height

- head length

- head breadth

- arm span

- sitting height

- left middle-finger length

- left little-finger length

- left foot length

- right ear length

- cheek width

Source: Wiki Commons, author: Roi Boshi. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

As part of this method, the police also recorded birthmarks, tattoos and scars (now known as “SMT”: scars, marks & tattoos) and took photos – the “original” mugshots – of the culprit. Also known as anthropometry, the system was a breakthrough in criminal identification and was widely used in Europe and the U.S. However, it was far from perfect; some individuals were just too similar in their proportions, and eventually it was replaced by fingerprint identification.

But still, Bertillon’s ideas – and especially the use of mugshots in criminal investigation – brought significant development to forensic science, and the criminal mugshot remains an important tool for law enforcement to this day.

Is facial recognition the modern Bertillon system?

While there are certainly differences between the Bertillon system and modern biometric facial recognition, both rely on the idea that individuals have unique physical characteristics that can be used to identify them.

The Bertillon system used a combination of body measurements and photographs to identify people, whereas biometric facial recognition relies solely on an individual’s facial features – such as the distance between the eyes, the shape of the nose, and the contour of the jawline – to create a digital signature that can be used to identify a person.

What is the chance of two fingerprints matching?

The chance of finding two identical fingerprints, according to Sir Francis Galton, is one in 64 billion. According to the Scientific American’s issue from 1894, “If, therefore, two finger-prints are compared and found to coincide exactly, it is practically certain that they are prints of the same finger of the same person; if they differ, they are made by different fingers.”

Fingerprinting: Put your finger on it

It was the year 1892 when Francisca Rojas was found wounded on the floor of her home alongside her two young children. The whole city of Necochea, Argentina was horrified by the attack, which claimed the lives of both of her children. Police initially suspected her neighbour of having carried out the attack, as was claimed by Rojas, but the neighbour’s alibi proved her accusation wrong. Officers were at a dead end, so they sent for Inspector Eduardo Álvarez to help find some clues.

Álvarez found a bloody fingerprint on the door. He cut out the piece of wood with the fingerprint on it, and contacted Juan Vucetich.

Vucetich was a police analyst who pioneered the use of dactyloscopy – the science of fingerprint identification. Although he couldn’t connect the fingerprint at the crime scene to the neighbour, it astonishingly matched Rojas, the mother. Under the weight of evidence, the woman confessed to killing her children because of her love interest. Apparently, he only wanted Rojas, not her kids.

Rojas’ case, although horrible, was groundbreaking because it demonstrated the value of fingerprints as a tool for identifying suspects and solving crimes, and it ultimately led to the widespread adoption of fingerprinting as a standard practice in criminal investigations around the world.

In the very early 20th century, the UK, U.S. and France started using biometrics – unique physical characteristics – for criminal identification, which marked the start of its widespread adoption. Every major police department in the world quickly caught on, and huge databases began to emerge. And by the 1920s, the FBI had created its first Identification Division – a central database for all U.S. law enforcement agencies.

Discovering the uniqueness of fingerprint

The science behind fingerprint identification can ultimately be attributed to two scientists. The first of them, Sir Francis Galton, was a British scientist and cousin of Charles Darwin who lived in the late 19th century. He was fascinated by the uniqueness and permanence of fingerprints and conducted extensive research on the subject.

Through his work, Galton proposed using fingerprints for identification purposes in law enforcement. His research became the foundation for the modern practice of fingerprint identification.

The second scientist, Henry Faulds, was a Scottish physician, missionary and scientist who noticed fingerprints on ancient pottery while working in Japan, and began to study their unique patterns. Faulds published his observations in the scientific journal Nature in 1880, several years before Galton’s work on fingerprints. Although Faulds’ work did not receive widespread recognition at the time, he is now considered an important contributor to the early history of fingerprint identification.

Sorting fingerprints

In the 1960s, there was a significant breakthrough in electronics with the emergence of the AFIS technology – Automated Fingerprint Identification System – a biometric solution consisting of a digital fingerprint database that was able to search and compare fingerprints. But how did they sort fingerprints before that? The answer lies in the Henry Classification System, which was a method developed in the late 19th century to organise and index fingerprints based on their pattern type.

Take a look at your hand. Do you notice whorls, loops, or arches? These were the key elements used for categorisation. The Henry Classification System was a significant precursor to AFIS, which is now evolving into ABIS – Automated Biometric Identification System. In addition to fingerprints, ABIS also supports matching iris and face data on a large scale.

Handwriting analysis: Beware your curves

In 2000, a woman named Susan Berman was found dead with a gunshot to the head. An anonymous handwritten card led police to her body, but there was too little physical evidence to solve the murder. Four years later, Berman’s stepson found letters from Robert Durst, her friend, which matched the handwriting on the anonymous card.

This discovery directed the police’s attention towards Durst. Although the matching handwriting on the letters was not enough to convict him at the time, fifteen years later, thanks to improvements in handwriting analysis, the police were able to provide enough evidence to arrest Durst and charge him with Berman’s murder.

Despite the fact that our handwriting is just as unique as our fingerprints, experts don’t seem to agree on whether handwriting analyses are legitimate sources of evidence. Many consider it unreliable and subjective, often calling it “junk science”. When used as evidence in court, it frequently comes under scrutiny, and the importance of it declines slightly with every email and electronic signature we use.

Nevertheless, handwriting analysis can be a very helpful tool when investigating potential forgeries of important documents, as every letter, curve, line and space between words, and even the number of pen lifts, are unique to every individual’s handwriting. Nowadays, handwriting analyses are often used when investigating handwritten wills and loan frauds.

How to read a fake

In a forensic investigation, handwriting analysis consists of three levels:

- First, the analyst looks at the writing as a whole. How does it look compared to the original? Does it look the same? Are letters the same width? What about spaces? Are proportions right? What about incline, etc. – these are called the gross elements.

- The second step is to look at the components of letters. How are the letters written and what are the sequences of strokes?

- The third level is the fine elements; very soft nuances like the quality of lines. Those are very difficult to see, and basically impossible to imitate.

Soft biometrics

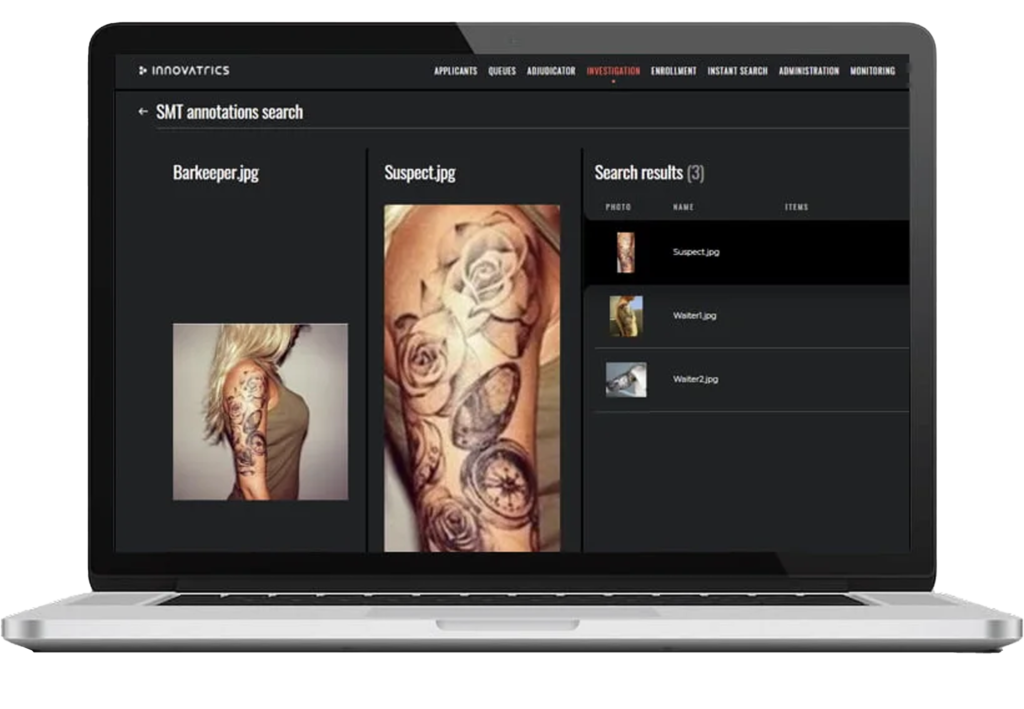

Scars, marks and tattoos are considered to be “soft” biometrics. So are height, sex, ethnicity or eye colour.

In order to help law enforcement identify suspects or victims when biometrics are not available or quality is low, Innovatrics has added a soft biometric database to their ABIS. Since 2021, investigators using ABIS are able to upload photos of SMT to the database and search for potential matches.

Unusual marks: Cover your flaws

In the early 19th century, the idea of all humans having specific marks and physical characteristics led to the founding of The British Registry of Distinctive Marks. It was an attempt to organise criminal records according to distinctive marks on the face and body, and would include birthmarks, freckles, tattoos, scars, but also any specific features like a missing finger, the unusual shape of a nose and so on. The records were categorised by the part of the body on which they were located.

The problem was, people usually had more than one such feature and so categorisation became difficult. The idea of a registry was eventually abandoned, but collecting information about special characteristics remained an integral part of criminal records.

This category is called SMT, which stands for scars, marks and tattoos. Thanks to the growing popularity of tattoos and other body embellishments, SMTs are increasingly used for suspect and victim identification in forensics. Tattoos in particular are more and more valuable for law enforcement because, apart from the visual aspect, they can also carry a lot of information about an individual’s interests, religious beliefs or affiliation to certain groups.

AUTHOR: Jana Nováková

COVER PHOTOS: Anthropometric system of Alphonse Bertillon. Measurement of the cubit, or length from the elbow to the end of the middle finger. Paris (France), 1894