“Proving guilt requires more than a fingerprint match,” says the director of the Institute of Forensic Science

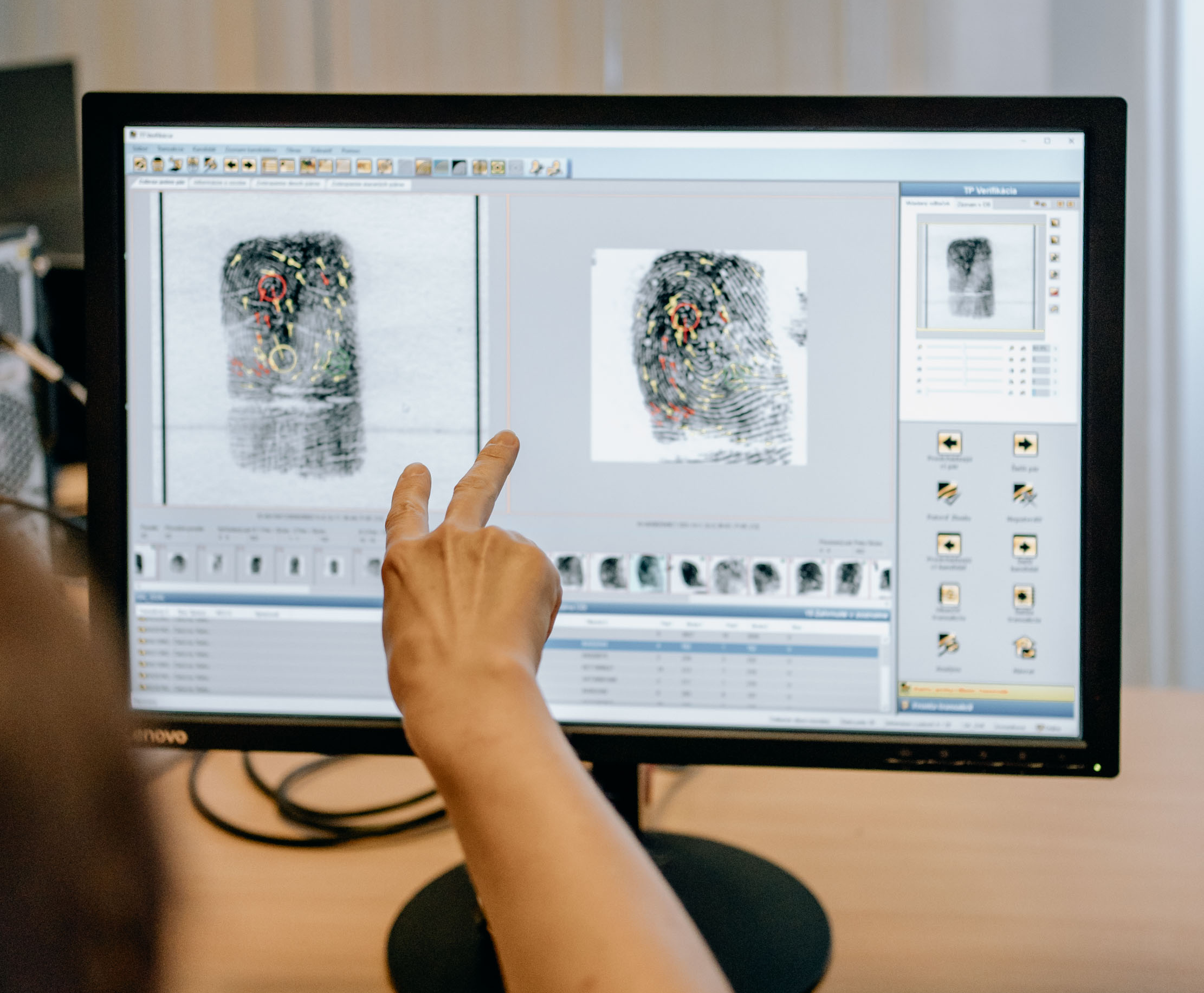

Biometric fingerprint identification has helped forensic experts in thousands of investigations. Yet, the fingerprint itself is just one piece of evidence evaluated by the court.

“Finding a match and proving guilt or innocence are two separate matters. We provide forensic expertise, but we do not interfere with the proceedings. Our conclusion is based solely on whether the fingerprints match or not, and for that, AFIS (Automated Fingerprint Identification System) has been a huge breakthrough,” says Zuzana Némethová, director of the Institute of Forensic Science in Slovakia.

Learn more about how automated fingerprint identification has changed the work of forensic experts, and how they utilise the technology within the rigorous processes they need to follow during criminal investigations.

You are the head of the Institute, which has more than 200 forensic experts. What is the role of a forensic expert in criminal investigations?

We receive requests from criminal investigators to provide expert opinions. As a forensic institution with expertise in over 20 fields, including forensic fingerprint analysis, investigators can ask our experts to analyse fingerprints, or they’ll submit items like glass, credit cards or flash drives containing fingerprints, and our task is to visualise and extract those prints from the items.

The expert evaluates the traces using various light sources, fingerprint powders or other chemicals to enhance the prints on the item. The expert then documents the prints.

The first step of analysis is to exclude prints that may belong to “known individuals”, such as people living or working at the crime scene who are not suspects. We then upload the remaining prints into the AFIS, where they are compared against the entire database. If necessary, we compare them with databases from other countries.

The search and analysis process always concludes with a certified fingerprint expert, trained in dactyloscopy, providing a professional opinion on whether a match exists or not, and preparing an expert report.

How many matching ridge characteristics must an examiner

find to confirm a fingerprint match?

There are as many as 150 ridge characteristics (points) in the average fingerprint. However, there is no universally set minimum number to qualify as a match, and it is up to the examiner to make the decision. Different departments and agencies may have their own criteria, which could include matching a specific number of points for positive identification.

Examiners consider factors such as the clarity and uniqueness of the fingerprint, as well as calling on their own experience. Less experienced examiners aim to match as many points as possible, while experienced examiners may be able to confirm a match with just a few points.

So ultimately, a human determines if the fingerprint matches are accurate.

Absolutely. We never provide the result of an automated database search without subsequent verification by an expert. We use a numeric standard to identify individuals based on a minimum number of matching ridge characteristics, and an expert always verifies the match.

Despite the existence of an automated system, it is still an international standard to create physical dactyloscopy cards.

You have witnessed the change from manual fingerprint analysis to digitisation and automation with AFIS. How did it change your work and the work at the Institute?

Prior to adopting the digital system for fingerprint identification, we only had manual databases filled with multiple dactyloscopy cards, which we classified using a specific system within the collections. So when a crime happened and we needed to analyse fingerprints, we had to search in databases manually, one print at a time, which was very time-consuming.

Not only does the AFIS system automate this process, but our system has also been connected to 21 other countries since 2008. So if we do not find a match in our database, we can access the databases of the other connected countries. Additionally, investigators can request Interpol to search their database as part of international police cooperation.

“I once had a case where an item from the crime scene contained three fingerprints. The investigator brought three suspects for comparison, but none of them matched. With the help of AFIS, we were able to match each of those prints to different individuals – who were unrelated to the initial suspects, and solve the case.”

How exactly does AFIS help experts with cases and expertise?

AFIS has helped us in hundreds, even thousands of cases. After the system was implemented, there was a tremendous increase in matches that the system found but experts had not previously discovered.

Prior to the system, we only compared collected fingerprints to those of individuals already identified as suspects by the investigator. However, in some cases it would not be possible to collect the suspect’s prints, or in others there weren’t enough leads to identify a clear suspect. Once we started uploading prints into AFIS, unexpected matches started popping up, even ones investigators were not aware of.

I once had a case where an item from the crime scene contained three fingerprints. The investigator brought three suspects for comparison, but none of them matched. However, with the help of AFIS, we were able to match each of those prints to different individuals, all of whom were unrelated to the initial suspects.

These individuals were already in the database, but the investigator had not connected them to the case. This breakthrough significantly propelled the case forward, and it was eventually solved.

Innovatrics’ ABIS is in testing phase

The Institute of Forensic Science and Innovatrics are working together on research and development projects. Experts from the Institute are currently testing Innovatrics’ ABIS – which helps identify fingerprints, static face images, and facial images from videos – in order to understand how ABIS works, provide useful feedback, and identify how it can be useful for the Institute’s work.

Automatisation started with AFIS but is now slowly shifting to ABIS (Automated Biometric Identification System). How is this transition unfolding?

From a process perspective, there has not been any difference. In practice, we still use AFIS, but we are prepared for ABIS. In other words, there is ABIS on the backend but the user interface is still AFIS. We have upgraded the system and laid the groundwork to fully utilise ABIS in the future.

Do your experts ever visit a crime scene?

When a crime scene is part of an expert investigation, such as a fire investigation, they go. They also go when it is necessary to provide scientific support at the crime scene. Once there, our experts act as scientific advisors and communicate with the investigator about the possibilities of evidence collection.

However, in such cases, the expert does not actively work on the specific case itself, nor are they involved in any of the analysis later on.

Automated Biometric Identification System Tailored to Your Needs

Innovatrics ABIS is a biometric identity management system supporting fingerprint, iris and facial recognition. Fast and accurate performance is achieved with minimal hardware requirements.

ViewHow do the experts advise on fingerprint collection at the crime scene?

The goal of fingerprint processing is to always make the print visible to the naked eye. About 30 years ago, we used a chemical powder called Argentorat, which consisted of aluminium powder, and we collected fingerprints using brushes.

Nowadays, we have various types of chemicals and powders available, with different adhesiveness, fluorescent powders, and colours that create the highest possible contrast with the background. In terms of chemistry, however, there is still room to experiment and discover new compounds and properties.

There are also special devices that can spot fingerprints in a room from afar, without any powders, such as ForenScope?

That has sort of always been the case. A fingerprint is essentially a deposit of chemical substances secreted by the skin. The trace naturally fluoresces, like any biological material, so it is all about how you illuminate it.

The Institute’s work includes a lot of sensitive information. When you receive a request to analyse fingerprints from a crime scene, how much information about the case are you given?

In the request, we get a brief description of the incident, such as stating that it was a theft. However, we do not have detailed information about what happened, as we do not usually visit the crime scene or collect evidence. So, the samples we work on are essentially anonymous to us.

Are you in the database?

In EU countries, biometric IDs have become a standard for personal identification. However, it’s important to note that these IDs are strictly used for individual identification purposes only. They are not stored in a central database, and the legislation in the European Union prohibits the use of these biometric records for criminal investigations by law enforcement agencies.

Let’s say an expert finds a match with the help of AFIS. Just how significant can this match be in court?

Considering that in Slovakia there is an open evaluation of court evidence, typically the court fully accepts the expert opinion from the Institute. Especially when each statement is based on an expert’s opinion, and not only the result of a system. We have not encountered a case where the court did not accept it.

However, it is also important to remember that finding a match is one thing, but filing a lawsuit, presenting the case in court, and proving guilt or innocence are separate matters. The fingerprint itself is just one piece of evidence evaluated by the court. We provide forensic expertise, but we do not comment on guilt or innocence or interfere with the proceedings. Our conclusion is solely based on whether the fingerprints match or not.

It is the same for facial identification. Even though it has not been automated yet, the analysis is carried out by a forensic anthropologist who is trained just like a fingerprint expert.

Do you utilise other types of biometrics?

We use various methods to analyse evidence, including voice, handwriting, language, DNA and body impressions. While some comparisons require manual analysis, we can always make a comparison if we have both the evidence and a comparative sample, such as the impression and the person identified by the investigator. Without a comparative sample, we cannot make a conclusive decision.

What about iris recognition? Is this type of biometrics used in criminal investigations?

Iris recognition currently does not provide added value for us. It is not visible on cameras and does not leave a print. The face is different. Apart from video footage, everyone also has a smartphone camera, and people often share their photos on social media. Iris recognition has more specific applications, such as access control to certain spaces, but even in those cases, fingerprints and faces are used more commonly.

What is the most significant development in biometrics at the moment?

Definitely face identification and recognition. In relation to the migration crisis in Europe, many regulations regarding biometrics were introduced, all of which focused on capturing fingerprints and faces.

Just as fingerprints were introduced and have become commonplace over the past 30 years, the same progression is happening with facial recognition. This is partly due to significant improvements in the development of facial recognition algorithms, which has been driven by higher demand for this technology.

Facial recognition is becoming increasingly common, much like fingerprints did in the past 30 years. The higher demand for this technology has led to significant improvements in facial recognition algorithms.

For instance, in the case of the London Underground bombings in 2005, the police were able to identify and locate the perpetrators through the use of camera systems. The extensive deployment of CCTV cameras allowed them to track the suspects’ movements. This was a scenario where facial identification proved valuable, as fingerprints were not available.

However, in the rest of Europe, such widespread use of CCTV cameras in public spaces is not possible due to legislative restrictions, where we are limited by GDPR laws.

Crime TV shows have been a popular trend for a long time. Considering your job, can you watch and enjoy them?

Sure, they are entertaining. As a rule, everything you see in a TV series is based on existing concepts, but it is exaggerated to make it more captivating. Nobody wants to watch four hours of a fingerprint expert searching for matches.

In TV series, everything usually works out perfectly – fingerprints match, DNA matches, the samples are high-quality and the suspect is conveniently waiting at home to be arrested. On top of that, there are multi-experts who can analyse handwriting, bones, voices, fingerprints and crime scenes… well, that is not how it works.

Has the public view of your work changed following the popularity of these shows?

There is a global trend known as the CSI effect, where people – including investigators – have high expectations about evidence analysis based on TV shows. They want methods they have seen on screen, but we have to explain that reality is different. At the same time, TV has made DNA analysis very popular, leading to an increase in requests for these assessments in laboratories.

Zuzana Nemethova, director of the Institute of Forensic Science, leads a team of over 200 employees who generate more than 25,000 expert opinions annually. Zuzana’s specialisation lies in fingerprint analysis and the use of AFIS (Automated Fingerprint Identification System). She has personally provided over 1,000 expert opinions in the field of fingerprint identification.

Zuzana also actively contributes to government initiatives and the development of legislation. Her involvement includes engaging with European Union proposals related to fingerprints, biometry and automated biometric processing systems. She is recognised as a valuable commentator on initiatives such as Eurodac, PRUEM, ECRIS-TCN, eu-LISA, and the Interoperability package.

AUTHOR: Jana Nováková

PHOTOS: Dominika Behúlová