From paper to digital: Modernising criminal records with biometrics

Contributors

Juraj Štubner

Project manager at Innovatrics (Guinea)

Alejandro Aleman

Solution Manager and Business Consultant at Innovatrics (Brazil)

Building upon the success of the first reliable voters’ list, which played a significant role in fostering fair and democratic elections, Guinea is now dedicated to modernising and digitising its police records. This involves the integration of biometrics into the criminal identification process, with the aim of increasing the number of solved crimes and preventing recidivism.

In Guinea, collecting and analysing fingerprints to identify criminals used to be rare. However, motivated by a strong desire to improve their work, the Guinean law enforcement, led by an enlightened police director, decided to implement the Automated Biometric Identification System (ABIS) from Innovatrics.

Where there’s a will there’s a way

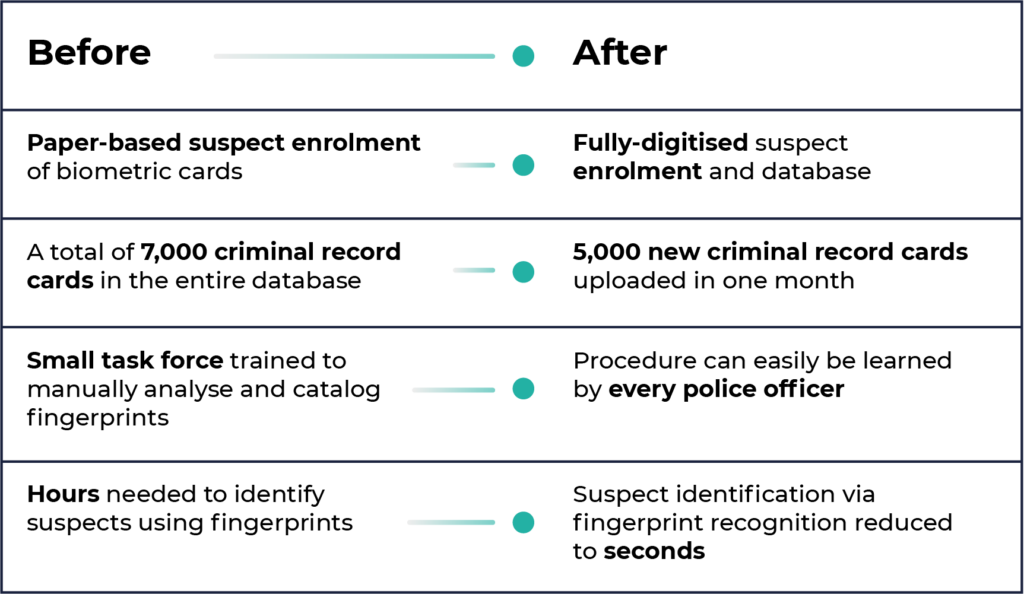

Even though Guinea is home to over 14 million people, a glance at the country’s criminal records revealed a number that raised a few eyebrows. “When we joined the project, the Guinean police only had about 7,000 paper-based criminal records containing fingerprints,” explains Juraj Štubner, project manager at Innovatrics.

This small number of records was partly due to the fact that the fingerprint-analysis experts were exclusively located in the country’s capital, Conakry, working for La police technique et scientifique.

Outside the capital, police didn’t work with fingerprints or any other biometric evidence. In cases where they were able to secure a suspect’s fingerprints or latent fingerprints from a crime scene, they had to send them in a paper form to Conakry for identification. The whole process could take days, even weeks.

“We wanted to create a solution that wouldn’t complicate the police’s job, and at the same time, would utilise the knowledge and skills the officers already have.”

The desire to better the process nationwide and make citizens safer nudged the Guinean police force towards action. “Law enforcement had a great ambition to improve and expand the capacity to work with fingerprints to other regions, which was a great starting point for us,” says Juraj.

The first step was to analyse the current situation, with the aim of then creating a solution that wouldn’t complicate the police’s job and, at the same time, would utilise the knowledge and skills the officers already had. That way the dactyloscopy experts in Conakry could remain an important part of the whole criminal identification process, with the only difference being that the process would become easier, faster and more accurate.

Juraj and his team had extensive communication with the local law enforcement to ensure that the ABIS would be custom-tailored to their specific needs. “We spent days just watching police officers work, and talking about what is important for them. Based on the gathered information, we created a system that works best for them,” adds Juraj.

Seamless migration of paper records

One of the key requirements of the Guinean police was to migrate the existing paper-based criminal records into the new system in a way that would be consistent with the new entries created in ABIS. “To tackle this, we designed the digital records in ABIS to align with the existing paper-based records format. This made digitising easier and more user-friendly than getting used to new record cards.”

“ABIS makes police work extremely efficient. The accuracy of biometrics allows us to prevent judicial errors and will greatly help us in administering justice.”

— Abdoul Malick Kone, General Director of the National Police in Guinea

This is how ABIS digitises the paper-based records: a paper record is scanned in order to obtain photos and fingerprints, the police officer enters the biographical data, and a new digital record is created. The whole process takes around 10 minutes per record.

Fully-digital enrolment in Conakry

Innovatrics has helped the capital Conakry to implement a fully-digital enrolment system for police records. Using biometric technology, the police can capture and store citizens’ information, including photos and fingerprints, within a matter of minutes. In the near future, the country will work on expanding this process to other parts of Guinea, improving record-keeping across the country.

Another requirement Juraj and his team had to manage was regarding mugshots. Guinean police take three shots of suspects and convicts: the half profile, front perspective and second profile. Since it is unusual in Europe to take three mugshots, Innovatrics created this feature in ABIS from the ground up. It was important to have a few iterations along the way, to ensure the final result made the police’s job as easy as possible.

Crime-solving through biometrics

Setting up the system was only the first part of the job – the second part was to empower police officers to collect biometric data and subsequently use it for criminal identification. In the past, the experts in dactyloscopy had to search through a manual database and compare suspects’ fingerprints, which took days. ABIS radically changes this concept.

The plan of the Guinean Police is to train officers across the country to gather fingerprints from suspects, and latent fingerprints from crime scenes, to get as much biometric material as possible.

Since digital enrolment is currently only available in Conakry, the regions should – for the moment – enrol their suspects on paper (in the same format as the existing 7,000 records) and regularly transfer the records to Conakry for digitalisation. Once digitised, they become part of the central database.

Making police work easier with ABIS

With ABIS, the capacity for analysis and identification has been increased manifold, and operations that would previously require many hours or days of work can now be executed in a matter of minutes or seconds. Meanwhile, the capacity for digitising the paper records with the current staff is up to 5,000 records per month.

The once-overwhelmed and limited police technique et scientifique now has the capacity to digitise and process the records and latent fingerprints coming in from all over the country, and ensure that every piece of biometric evidence is compared against all the available database records.

Automated Biometric Identification System Tailored to Your Needs

Innovatrics ABIS is a biometric identity management system supporting fingerprint, iris and facial recognition. Fast and accurate performance is achieved with minimal hardware requirements.

ViewIn addition to comparing the latent fingerprints with the database records, the database itself also actively undergoes permanent deduplication. This deduplication process merges repeating records that were previously treated as separate identities, allowing for identification of false identities. In terms of investigation capacities, this represents a genuine revolution.

“The once-overwhelmed and limited police technique et scientifique now has the capacity to digitise and process the records and latent fingerprints coming in from all over the country.”

This upgrade is a promising step forward for a country with a high rate of organised crime, homicides, and easy access to weapons, as reported by the Global Peace Index 2022.

Facts about Guinea

Based on reports by the Global Organized Crime Index, the biggest threats of the Guinean criminal market are human trafficking, arms trafficking, cocaine trade, non-renewable resources crimes and crimes concerning local fauna.

Guinea is sometimes known as Guinea-Conakry in order to distinguish it from other countries in West and Central Africa with the Guinea name, such as Equatorial Guinea or Guinea-Bissau.

The country is rich in minerals. An estimated quarter of the world’s bauxite can be found here, as well as iron ore, diamonds, gold and uranium.

Overcoming cultural challenges

“It is always great to be on-site when it comes to projects in emerging or developing countries. Sometimes, it can be difficult to understand the conditions of work until we are here. For example, some of the things we tend to take for granted outside of Africa may be problematic to do here,” admits Juraj.

Guinea is among the countries with the lowest digital literacy in the world (in 121st place out of 134 countries on the list), so even working with computers could sometimes be a challenge.

“Some officers have never worked with computers or keyboards, so we had to teach them first. Luckily, we had a few quick learners who, within a week, were training their colleagues,” he adds.

Power outages were also usual, which made online training complicated. “Of course, we encountered some difficulties as well as cultural differences, but fortunately, most officers were eager to learn,” says Juraj.

After successfully implementing ABIS, the project continues to the next phase, which is the deployment of facial recognition software.

Connecting the biometric dots in Brazil: How an innovative algorithm for children’s fingerprints can potentially assist in solving child trafficking cases

In Brazil’s diverse landscape, each of its 26 states issues its own IDs and driver’s licenses. This results in a scenario where it is completely legal to have 26 different pieces of documentation. However, the states issue documents under different providers and their databases often fail to communicate with each other. Maranhão, a northeastern state with a population of 7 million people, was just one of the many states facing this challenge.

“Maranhão was the first Brazilian state we helped to synchronise databases and introduce new tools for both collecting and identifying biometric data such as fingerprints,” says Alejandro Aleman, Solution Manager in Innovatrics who worked on the project.

With their local partner Valid, Innovatrics discovered several issues: the biometrics the state already used were obsolete, fingerprint processing was inaccurate and slow, and duplicates in databases and children’s fingerprints were both causing false matches.

So how exactly did Innovatrics help? Let’s break it down step by step.

- Deploying ABIS for driver’s license issuance and criminal identificatio

In Maranhão, the police had limited criminal data because driver’s licenses and criminal records were stored separately. However, with the new ABIS system, both databases are now connected. Alejandro explains, “We transferred the legacy databases into the new system, which provided the police with valuable data but also brought new challenges to the project.” - Managing duplicates

Combining the databases unveiled numerous duplicates, especially due to errors and obsolete tools. Duplicates in databases slow down police work because the system has to search through millions of entries to find a match during the identification process. Thanks to the automatic tool that detects and deletes duplicates, Alejandro and his team were able to reduce the number of entries from 5 million to 10,000. - Creating categories for simpler identification

In order to simplify the search, new categories were created. Police are now able to label database entries under civil or criminal categories. A special category has also been created for children. - Children’s fingerprints

Children’s fingerprints are a special category ABIS had to deal with: “They are small, so the papillary ridges are very close to each other and so are the minutiae points that are used to map out the fingerprint,” says Alejandro, “These points are so close to each other, that they confuse the system and match with almost any adult fingerprint.”

To overcome this, Innovatrics developed a special algorithm that automatically scales the fingerprint resolution based on the distance between papillary ridges. In the future, this innovative algorithm can potentially assist in solving child trafficking cases and help with victim identification. - New option for uploading SMTs and videos

One of the upgrades that Innovatrics brought to the criminal ABIS for Maranhão was the ability to upload and search images of distinctive marks like scars, marks and tattoos (SMT), which can be a valuable part of the identification process. Another possible option was to upload videos onto criminal records to make the search for potential criminals easier.

The Maranhão project took 18 months to complete, and its success has inspired other Brazilian states like Espírito Santo and Rio Grande do Sul to also embrace ABIS technology from Innovatrics.

AUTHOR: Jana Nováková

ILLUSTRATIONS: Julia Latusek