Five questionable cases of election fraud and how they could’ve been avoided

Deceased people still registered to vote, bad ballot design or even honest mistakes can raise eyebrows about the integrity of elections. Even more so in these times, when it has become easy to enrage the masses into believing the system is crooked – as we saw in the US after the 2020 presidential elections, when Donald Trump, who lost his seat in the White House to Joe Biden, was able to incite mistrust to the extent of causing a Capitol riot.

When it comes to voter fraud, there seems to be no clear consensus about what the phrase actually means. One of the clearest and most logical definitions, as described by the Brennan Centre for Justice at New York University, is that “voting fraud occurs when individuals cast ballots despite knowing that they are ineligible to vote, in an attempt to defraud the election system.” Still, the realities and consequences of the wider topic of voter fraud are not quite so simple.

It has been a challenge for many governments to create elections that are safe and fair for everyone. However, modern technology – specifically, biometrics – can in many cases ensure that every voter’s voice and choice is unique and true, whether dealing with in-person fraud, double voting, large-scale scheming, or even accidental fraud. Read about five questionable cases of election fraud that have really happened and find out how the use of technology could’ve prevented them.

Big schemes and manipulation concerns

Robert Mugabe, former prime minister and then president of Zimbabwe, had the world divided after the country’s 2013 election. He won with a majority of 61% of the votes and his party Zanu–PF gained two-thirds of the seats in the parliament. Western observers were banned from the elections, and Western countries condemned the results. African monitors pointed out some irregularities, but overall praised the elections as peaceful and fair.

The opposition accused the administration of massive fraud, claiming that the generated voters’ list has been a “systematic effort to disenfranchise an estimated one million voters.”

In rural areas, where Mugabe’s party electorate typically resided, almost 100% of voters were registered to vote, compared to less than 70% of voters in urban areas, where the opposition – Movement for Democracy (MDC) – had stronger support. The excuse given by Mugabe’s party was that the registration in urban areas was more complicated than in rural areas.

The opposition also found 838,000 entries with the same name, address and date of birth but different ID numbers, and more than 100,000 people aged over 100 – including a 135-year-old army officer. The BBC also confirmed it had seen a copy of a constituency roll from Harare with duplicate names listed. The election outcome? Mugabe remained president, until 2017 – when he was ousted in a coup by his own party and resigned as president and party leader.

Bulletproof voter registers, thanks to biometrics

If a country’s officials are truly ready to align with the values of democracy, biometrics are here to help. A voter register based on biometric technology detects and removes all duplicate registrants from the list. De-duplication is particularly useful when citizens cannot prove their identity with reliable documentation, when civil registries are incomplete or have a high proportion of mistakes, or when the quality of data in the voter register is low.

Families overstepping the boundaries

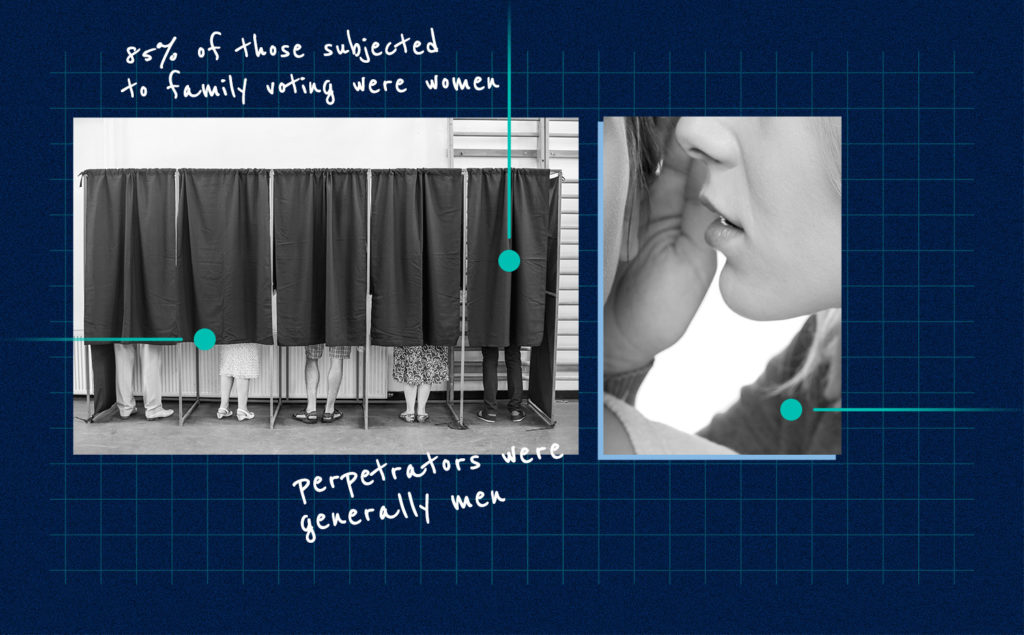

Every voter has the legal right to cast a private vote. After all, that’s why most voting booths have curtains or some other form of sight barrier. Still, a phenomenon called family voting – where one relative directs and influences other family members on how to vote, often by physically entering the voting booth with them – haunts even the most developed countries such as the United Kingdom.

During the UK’s council and mayoral elections in spring 2022, Lutfur Rahman was elected Mayor of Tower Hamlets, a district in the east of London. However, after the elections, a report observing “extremely high levels of attempted family voting” was released by an independent electoral monitoring group, Democracy Volunteers. Around 85% of those subjected to family voting were women, and those behind the family voting were generally men. The Electoral Commission condemned the actions, claiming that “anyone attempting to influence how another person votes – including close relatives – is breaking the law.”

Tower Hamlets is the most recent example of how family voting is still a likely problem, not only in the rest of the UK but also globally. Democracy Volunteers reported instances of family voting in the Netherlands, Sweden, and during a Gibraltar referendum.

Biometrics can prevent family voting

Even though biometric authentification is a technological solution and its deployment can hardly influence somebody’s morals, installing an electronic identification system in all voting centres can greatly mitigate the risk of double voting, family voting or voter impersonation. Such observations were repeatedly confirmed by independent election monitors all over the world.

Butterfly effect

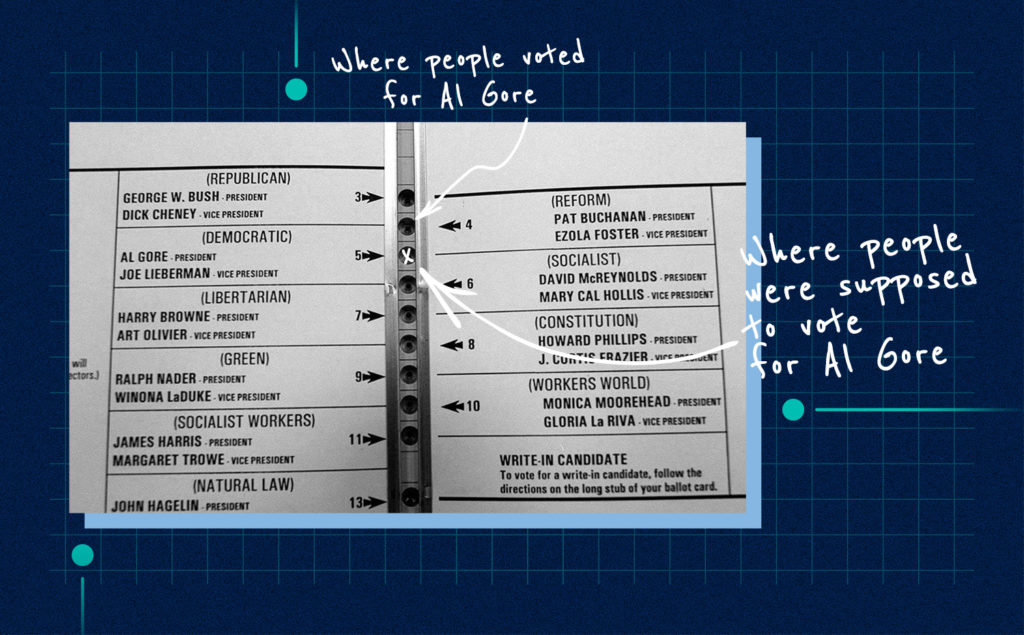

During the 2000 presidential election in the US, Florida’s voting was marred by a number of problems – the most famous one being the “butterfly ballot” used in Palm Beach county, where, because of its bad design, a number of voters mistakenly ended up voting for the wrong candidate. Research by Stanford Graduate School of Business showed that more than 2,000 Democratic voters accidentally voted for Reform candidate Pat Buchanan.

The devil lies in the detail, and this detail turned out to be a very important one. The space that voters were to mark in favour of their candidate was not aligned with the row of the candidate. As a result, George Bush won a 537-vote margin, which ultimately cost Al Gore the presidency. Some aspects of the ballot design in the US have been refined, but there is still room for improvement.

Online voting to the rescue

Bad ballot designs are easily prevented by voting online, as voters usually click directly on their chosen candidate’s name and are also prompted to confirm before finalising their vote, eliminating any risk of confusion or unintentionally voting for the wrong candidate. Requiring eligible voters to come to a certain location to cast their vote can also result in many physical barriers and unnecessary bureaucracy, which online voting also addresses – as all eligible voters can simply use any electronic device to vote, and do it safely from any location.

The dead can’t vote. Or can they?

In developed countries, committing fraud by voting in the name of deceased people is rare – but it can happen, and from time to time it does.

One such instance occurred in 2017 when Toni Lee Newbill, a Colorado woman, pleaded guilty to voting in the 2013 general election and in the 2016 Republican primary in the name of her father, who died in 2012. Newbill tried to remove her father’s name from the voter list, but wasn´t successful, and so decided to use his ballots to cast additional votes. However, the El Paso County Clerk and Recorder office had already sent Newbill a form to have her father removed from the voter list in January 2015. Newbill received a $500 fine and was sentenced to 30 hours of community service and 18 months of unsupervised probation.

Using deceased people would be impossible

Authentication of eligible voters is critically important. Since biometrics collect and store unique physical or behavioural characteristics, such cases as the one mentioned above could easily have been prevented. For voter registration, biometric data for every eligible voter is captured, with the resulting voter-register containing irrefutable unique data such as fingerprints and facial images in addition to biographical and relevant personal information.

Phantom threats and the need for modernisation

It’s not only illegalities that create problems and a threat to democracy; a phenomenon called the phantom threat that fraud “may” happen is just as capable. It is therefore important to identify the scale of this problem, as mere signs of fraud make many eligible citizens reluctant or unable to vote, and without knowing the scale, it is harder to find a solution.

Truth be told, it is very hard to wilfully commit voter fraud, and many cases of alleged fraud are in fact mistakes by either the voters or administrators.

But how can an exaggerated premise of election fraud complicate people’s access to voting? “Claims of voter fraud are frequently used to justify policies that do not solve the alleged wrongs, but that could well disenfranchise legitimate voters. Overly restrictive identification requirements for voters at the polls – which address a type of voter fraud that is rarer than death by lightning – is only the most prominent example,” claims the Brennan Centre for Justice.

Fraud exaggeration can also lead to some deplorable consequences. In the US, a legal Florida resident, Usman Ali, was deported back to his native Pakistan because he improperly filled out a voter registration card when he renewed his driver’s license. Ali checked the “yes” box to register to vote while applying for a driver’s license. He never voted, and yet was still deported for alleged voter fraud, after 20 years of living in the US.

In another case, Rosa Maria Ortega, a permanent Texas resident and a mother of four, got eight years in prison and certain deportation after illegally voting twice. This case is unusual, as very few fraud convictions get any prison time, and those that do have normally clearly attempted to influence the elections. But Ortega testified that “she didn’t know that she was ineligible to vote and was confused by the registration forms and explanations by election officials,” yet still received this harsh sentence.

Both scenarios show that discrimination or other extreme and unwanted repercussions can result from the very threat of election fraud. Elections in any state should be able to withstand any suspicions or concerns. Therefore, to make it both safer and more credible, it’s important to modernise and simplify the methods we use in elections. Biometrics are a highly advanced technology that can help with such a challenge, as the solutions it provides are very human, yet extremely hard to fool.

AUTHOR

Nikola Šuliková Bajánová

PHOTOS

Shutterstock

Butterfly Effect

SOURCES

Voter Fraud in the US?

Zimbabwe: A guide to rigging allegations

The Myth of Voter Fraud

Voter Fraud

Biometric Technology in Elections

Modernize the voting process

Dead people vote too

Bad ballot design

The Butterfly Did It

The voter fraud fantasy

Voter Fraud: Non-Existent Problem

New ‘crackdown’ on family voting

Illegal Voting