Carpooling in wartime

and spare air mattresses:

a visual history

of the sharing economy

From gathering food to downloading popular MP3 songs, sharing is something humans have always done. Join us on a visual journey through the decentralised economy and discover how technology has revolutionised the way we share.

A huge stone. Probably the first thing ever shared.

In the annals of history, a single stone probably holds the title of being one of the earliest shared resources. Archaeological records unveil the story that unfolded in Kanjera, Kenya. There – about two million years ago – early humans dragged an enormous stone over 12 kilometres to their chosen site. This was no ordinary rock: it was shared with fellow tribe members for crafting essential butchering tools.

Sharing is part of the social life of humans. In bygone eras, huddled around the warmth of a fire, our ancestors shared much more than just food; they exchanged tools and knowledge, fostering cooperation to meet the challenges of a harsh environment. Leaping to the 20th century, sharing also manifested itself on multiple levels: from neighbours swapping a lawnmower to hitchhiking to vintage laundromats. This is when new information technologies began to reshape the way we share.

To illustrate the progress that gave way to the evolution of the sharing economy as we know it today, we created a visual timeline mapping its rising popularity since WWII all the way to the present day, when the sharing economy has become ubiquitous and its boundaries hard to define.

Carpooling in wartime.

A phone call, a paper map and some pins.

The Second World War brought with it a time of many changes, including a new need to share. To conserve rubber, petrol and vehicles for the war effort, carpooling was born during these harsh times, when the US Office of Civilian Defense introduced a special club – the Car-Sharing Club Exchange – and a so-called Self-Dispatching System. Poignant billboards helped communicate the new idea: ‘When you ride alone, you ride with Hitler’, they warned.

During the 1970 oil crisis, car sharing then made a comeback. This time signing up was managed via a phone call, while staff marked locations on a paper map with pins. Meanwhile, President Nixon approved federal funding for car-sharing initiatives.

The first listing on eBay

For decades, garage sales and flea markets were the way to offload unwanted items. Then, in the mid-1990s, the internet opened up a new opportunity for selling underused goods. Legend has it that Pierre Omidyar created eBay to rid himself of his wife’s collection of Pez dispensers, but in reality, the first item put up for sale on eBay was a laser printer (listed for $1). Craigslist – the popular website for classified ads – was born in the same year.

Platforms began to rely on feedback mechanisms, user reviews and star ratings, revealing a fundamental need for trust to succeed and operate effectively.

How to share a song: Napster’s rise and fall

A revolutionary technology made sharing digital files – especially MP3s – easier than ever. Peer-to-peer (P2P) technology did away with the need for a central server, instead harnessing the power of millions of interconnected peer computers over the internet. This enabled the universal sharing of media – or, at least, it let you download your favourite love song.

While not the first to use the P2P protocol, Napster is certainly the most sensational example. Born from the ingenious mind of a barely nineteen-year-old Shawn Fanning, the software offered millions of users effortless access to free music and more. College networks were soon congested with file transfers, but legal troubles loomed. By 2001, Napster had succumbed to countless copyright lawsuits, and eventually filed for bankruptcy in 2002. Today, Napster remains a controversial symbol of the early sharing era.

Airbnb and the tale of three spare air beds

In the midst of the Great Recession, a new sharing platform made its debut: Airbnb. Two roommates came up with an idea to add three inflatable beds to their living room, essentially creating an impromptu bed-and-breakfast. The following year, a third co-founder joined the team and a new website was born: Airbedandbreakfast.com. The platform proved particularly valuable to attendees of the Obama Democratic National Convention who were struggling to find a place to stay in packed San Francisco.

Peer-to-peer accommodation was a simple concept – people could rent out their extra space to travellers. It also allowed travellers to experience destinations in a more local and personal way. As investors became interested in the idea, a new term – namely, the sharing economy – entered the public discourse.

The first-ever Uber ride

in San Francisco

While the concept of ridesharing had been around for some time, in 2009, a mature technology changed everything – once again. You could now get a ride simply by tapping on your smartphone.

The first ride ordered via a smartphone app – at the time called UberCab – took place in San Francisco: it was a rather luxurious limo transfer. Along with rivals like Lyft, which launched in 2012, Uber reshaped how we think about getting from point A to point B in our cities by using peer-to-peer drivers – and disrupted the traditional taxi industry. Ironically, the initial idea for Uber was born when the two founders found themselves stranded without a taxi on a cold night in Paris.

The expansion era

The 2010s saw the rapid expansion of the sharing economy, transforming both industries and consumers’ habits.

In December 2011, Uber launched its services in Paris, marking the start of its international rollout. In 2015, Airbnb made a historic move by launching its operations in Cuba, becoming the first American company to do so. The success of sharing economy services inspired new, creative ideas. Both tech giants and one-person projects enabled the peer-to-peer exchange of all kinds of things: from fashion (Poshmark, Vinted) to entertainment (Spotify, Netflix), finding a garden to pitch a tent in, or renting desks in exclusive coworking offices. Not least, food delivery – in 2015, the number of online orders surpassed phone orders.

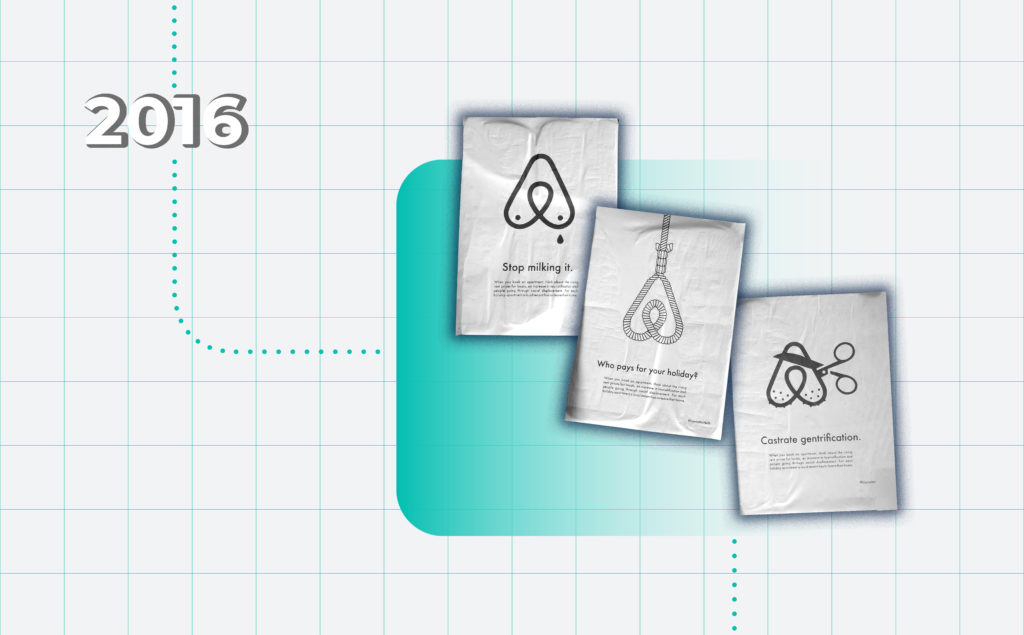

Bans, boycotts and strikes

As sharing economy platforms continued to grow, they came with their fair share of controversy. Challenges revolved around issues such as regulatory compliance, labour rights and safety concerns. While born with the intention of unlocking untapped resources, these platforms also brought both anticipated and unforeseen consequences to society.

Taxi drivers, feeling the pressure of peer-to-peer services as a significant threat, staged violent protests. Cities saw an increase in strikes by food delivery workers. Long-term rental markets started to suffer as a result of higher-yielding opportunities, leading to bans on short-term rentals via home-sharing websites in certain cities, and anti-Airbnb billboards appearing in Berlin. As the user base of these platforms grew, issues of trust and accountability also intensified.

Sharing in the time of the pandemic

As the Covid-19 pandemic swept across the globe, it brought a wave of uncertainty: no one was ready. Was sharing still possible in a world marked by social distancing, closures and economic upheaval? Although some believed that the crisis might actually reinforce the basic principles of the sharing economy – those of fostering community cooperation and peer-to-peer trust.

The economic impact of the pandemic forced the unicorns of the sharing economy to adapt to new norms swiftly. Innovative technologies, workflows and ideas became essential: platforms began offering contactless dining experiences and delivering essential items during lockdowns. Notably, Uber expanded into food delivery to offset the temporary decline in demand for ride-hailing.

The future of the sharing economy

From ridesharing to delivery platforms, today, the sharing economy is ubiquitous. And it has become hard to define its boundaries.

Does decentralised information sharing – as happens on Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter) and other major social networks – fall within the realm of the sharing economy? On the other hand, blockchain-enabled innovations allow all kinds of transactions to be validated through peer-to-peer protocols – potentially without the need for a central notary – from contract signing to licensing.

In 2021, more than 86 million consumers in the US alone used some type of peer-to-peer sharing platform. In that year, the sharing economy was worth USD 133 billion, and some forecasts suggest it will reach a staggering USD 600 billion by 2027. So, what lies ahead?

AUTHOR: Giovanni Blandino

PHOTOS: Shutterstock

Sources

- Human Characteristics: Social Life

- The Inside Story Behind the Unlikely Rise of Airbnb

- History of eBay: Facts and Timeline

- The evolution of Airbnb regulations

- COVID-19 Impact on the Sharing Economy Post-Pandemic

- The ‘sharing economy’ lacks a common definition

- Value of the sharing economy worldwide in 2023 with a forecast for 2027 and 2031