The way we used to bank:

a nostalgic voyage through the past decades of financial technology

Nonstop innovation has shaped the way we think about banking and finance in the last decades, but also influenced how we perceive trust and technology.

From the first cardboard credit card to a pioneering 80s-style videotex terminal, the path that led us to modern banking technologies is full of obscure prototypes, iconic objects, sketches of breakthrough ideas and essential little inventions.

Things change constantly. Virtual banking was a talked-about novelty 20 years ago; now we are all used to it. New York stores in the 1950s trusted a charge-card made of paper with a signature on it – would you trust that today? Looking at the curious past of financial technology, it’s easy to imagine that advancements and innovation are soon going to change the way we see the banking devices in use today.

Let’s discover the way we used to bank, starting from the very beginning of the story.

Facial Recognition for Real-World Situations

Innovatrics has been developing facial biometric algorithms that consistently rank among the best in the world in terms of accuracy and speed based on independent NIST benchmarks. We’ve scored top marks in the Wild Images category — generally considered the most critical area for facial recognition technologies.

Send money abroad, with the Templars!

Back in the Middle Ages, travelling was everything but a safe affair. Pilgrims heading to the Holy Land set off for long, perilous journeys in foreign lands, and they had to carry enough money to pay for their food, transport and accommodation. They were the ideal targets for robbers and bandits of all sorts hiding along the way.

Luckily for the pilgrims, the Knights Templar – back then, the most glorious order warrior monks in Europe – came up with the perfect solution. Before the departure, pilgrims could visit a Templar house in their home country, deposit deeds and valuables… and withdraw cash once arrived in Jerusalem (or in posts along the way). Instead of carrying unsafe money, pilgrims could just keep a letter of credit in their pocket.

That’s right, it seems that the Templars invented the first international money transfer – which had the interesting side effect to increase by means their power in Europe.

How all this worked is still cloaked in mystery. Some scholars suppose that the letters of credit were encrypted with cipher alphabets, storing required details about the pilgrims’ holdings. What we do not know for sure is how the Templars protected themselves against fraud and how they verified the identity of the letters’ holder. Hidden under dusty robes and after months of struggles, who could really recognize the face of a pilgrim?

How to pay your supper with a signed piece of cardboard. The first credit card.

Year 1949, New York City, evening. The businessman Frank McNamara is dining with his clients at the Majors Cabin Grill restaurant, suddenly he realizes he has left his wallet in another suit. He flushes red with embarrassment — What a shame! — and askes his wife to set the bill for him.

Minutes after the incident, McNamara has already decided it should never happen again. This is when he came up with its idea: a multipurpose charge card. At that time in New York, many stores already used to extend small amounts of credit to regular customers. Yet, McNamara’s idea was to use only one card to pay for purchases in different stores.

The year after, McNamara went back to the same restaurant with his business partner. This time he paid the supper with a small, signed cardboard card. That was the Diners Club Card: the first-ever credit card.

The Diners Club Card would allow patrons to settle their bill at the end of each month through their credit account. When the card was first introduced, 200 fine gentlemen among McNamara’s acquaintances could use it in 27 restaurants. By the end of the year, Diners Club had 20.000 members.

How could people trust a cardboard piece with a signature on it? If it shocks you, you should also consider that still today we put a lot of trust on our autograph while, out there, there are better ways to authorize documents and stuff.

Something like a chocolate dispenser, but with cash. The world’s first ATM

“There must be a way I could get my own money, anywhere in the world or the UK”. Trying to solve this unfortunate problem while tacking a bath, the Scottish inventor John Shepherd-Barron came up with his sketch idea: a chocolate bar dispenser, with cash instead of chocolate.

At that time — it was the mid-60s — John Shepherd-Barron was working for a printing firm. He soon went to pitch his idea of the new cash device to the British bank Barclays, they accepted it immediately. For years, financial institutions had been looking for an automated way to let customers perform transactions — cash withdrawals, deposits, funds transfers — at any time and without the need for human interaction or staff. Unfortunately, some previous, highly creative, ideas experimented in the decade lacked customer acceptance.

The first ATM based on the sketch of John Shepherd-Barron was built and installed in Enfield Town, North London, on 27 June 1967 with the popular entertainer Reg Varney being the first person to withdraw cash from the shiny, new machine.

To initiate a withdrawal, customers should have inserted in the device checks which were impregnated with isotope carbon 14, a slightly radioactive substance that enhanced machine readability and security. Later machines used PIN codes for the verification which, coupled with magnetic stripe cards, is basically the same way we withdraw money from ATMs today.

How much longer are we going to rely on PINs?

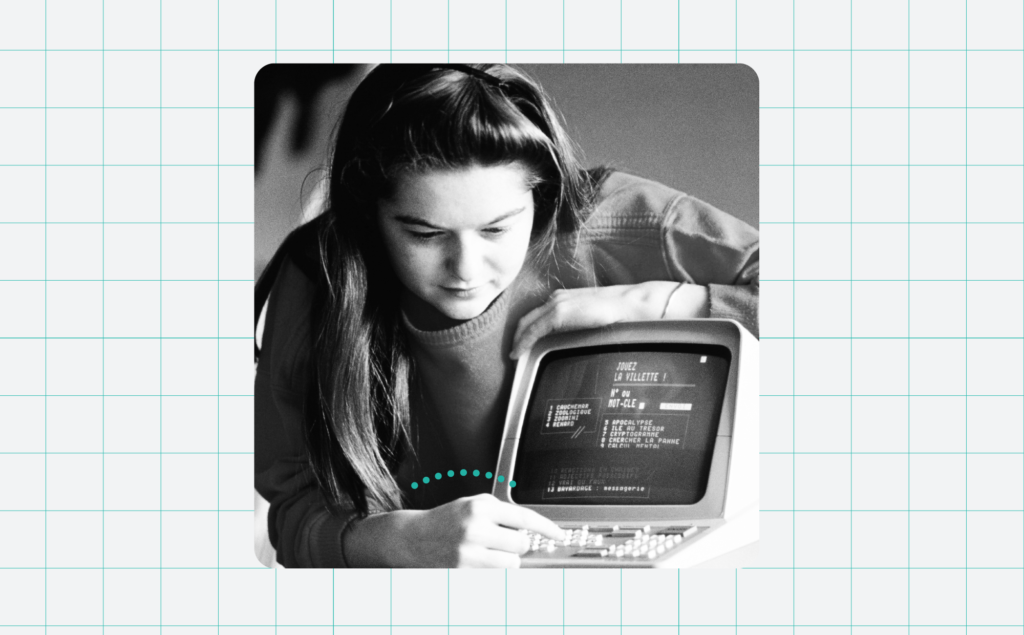

The incredible French 80s: pioneering online banking via videotex.

A decade before the Internet became popular all over the world, France had already its own fully functioning ubiquitous network: the Minitel.

The Minitel was a marvelous technology: an open videotex service accessible through telephone lines, entirely managed by the state. Along with the subscription to the French telephone, citizens received for free their terminals — modern, sharp boxes with a text-only monochrome screen and a keyboard. This is how, since 1983, the French have been able to make online shopping, reserve tickets online, check stock prices, search the telephone directory, have a mailbox, and chat; all in a similar way to what is nowadays made possible by the Internet. There was even an archaic form of online porn and adult messageries. And, of course, there was also banking.

For the first time, bank customers could send instructions to their branch simply using their visual terminals at home. Financial services benefited from Minitel’s security features — users could log into dedicated access points — and its secure access to professional databases, paving the way for what would soon become known as online banking.

In the late 1990s, despite the growing use of the World Wide Web, Minitel connections were stable at 100 million a month. This makes the network the world’s most successful online service before the World Wide Web!

Embedded Solutions Portable to Any Hardware of Today

Our top-ranked algorithms provide instant extraction, verification and identification even on constrained hardware, like PoS terminals, smartphone or smart locks.

Your bank in a Palm: early mobile banking via WAP

By the mid-1990s, millions of people over the planet could access the Internet. Yet only from their home computers. Cell phones, meanwhile, had become widespread; and among the must-have items for the successful businessman in the New Millennium, there were the Organizer, the Palm and all the other so-called personal digital assistants (PDAs). Believe it or not, they were quite hip back then!

The problem was that people needed the Internet on their new mobile devices which actually were too short on resources to handle the HTTP standard. This is why, in 1997, the leading cell phone companies in the 90s — Nokia, Motorola and Ericsson — got together to develop the WAP: an open, universal standard delivering the Internet to the growing number of mobile devices.

Their cell phones – still with small, low-res displays and slow EDGE or GPRS data connections – began to use WAP browsers to access wap-sites. Many companies, in addition to the normal HTTP websites, started to open dedicated sites for mobile users. The count was increasing every single day because the use of WAP all around the world had become very popular. Banks, of course, were among first companies moving to mobile.

The first bank group that launched WAP banking services was MeritaNordbanken from Finland. It was 1999. Their customers — as the company proudly announced it — were the first in the world to be able to handle their banking business via WAP phones. From that moment on, using your “WAP terminal” – a.k.a your cell phone – you could monitor your account, check your credit card transaction, pay your bills and transfer money from account to account.

Banks could finally, and correctly, claim that they were at customers’ disposal… wherever they were.

CASE STUDY: Retail Bank Onboards New Customers Fully Online

At the bank branch, it took at least 45 minutes to open an account. Clients had to submit a number of documents and certify their authenticity by affixing their signature. Now the retail bank onboards new customers remotely in just 2 minutes.

Gone online: the first-ever virtual banks.

1999, end of the century. The millennium bug hysteria mounted, Baby One More Time by Britney Spears was a No 1 hit, the Dot-com Bubble was ready to burst. It was at that time that the first internet-only banks appeared in Europe: they were called First-e, Smile and Egg Bank.

Direct banks in Europe were something completely new. They had no traditional infrastructure, no branches, no offices: they were virtual. Reducing staff and offering services remotely – via Internet, mail or mobile – thanks to the fast-paced digital growth, virtual banks managed to cut significant costs. This allowed many of them to offer savings accounts with higher rates and loans with lower rates than most traditional banks.

“No queues. No closing times”, claimed the earliest advertisements. However, consumer hesitation was there. How could they trust a bank they cannot deal with face-to-face? Luckily for internet-only banks, today a growing digital culture and more secure online tools are constantly building up trust and confidence towards only-online services.

AUTHOR: Giovanni Blandino

PHOTOS: Shutterstock, Alamy