Biometrics to the rescue: helping democracies to build elections that can be trusted

The number of democracies in the world is shrinking. Many countries are struggling on a precarious path between democracy and autocracy. Long-established Western democracies’ fears over the denial of election results are becoming more and more frequent. Building trusted elections takes a number of firm political and social actions. But in many cases, biometric technology can be a big step forward in helping to secure more credible and reliable voting processes.

The majority of the world’s countries are democracies, and billions of people enjoy basic democratic rights: the right to vote or the freedom of speech and opinion. Undoubtedly, democracy represents a great success for humanity. But if we look back at the world as little as 200 years ago – when French revolutionaries had just stormed the Bastille crying for liberty, equality and fraternity – things were quite different. Modern democratic regimes as we know them today were still in their infancy, with pretty much the entire world’s population lacking democratic rights.

How many democratic countries are there?

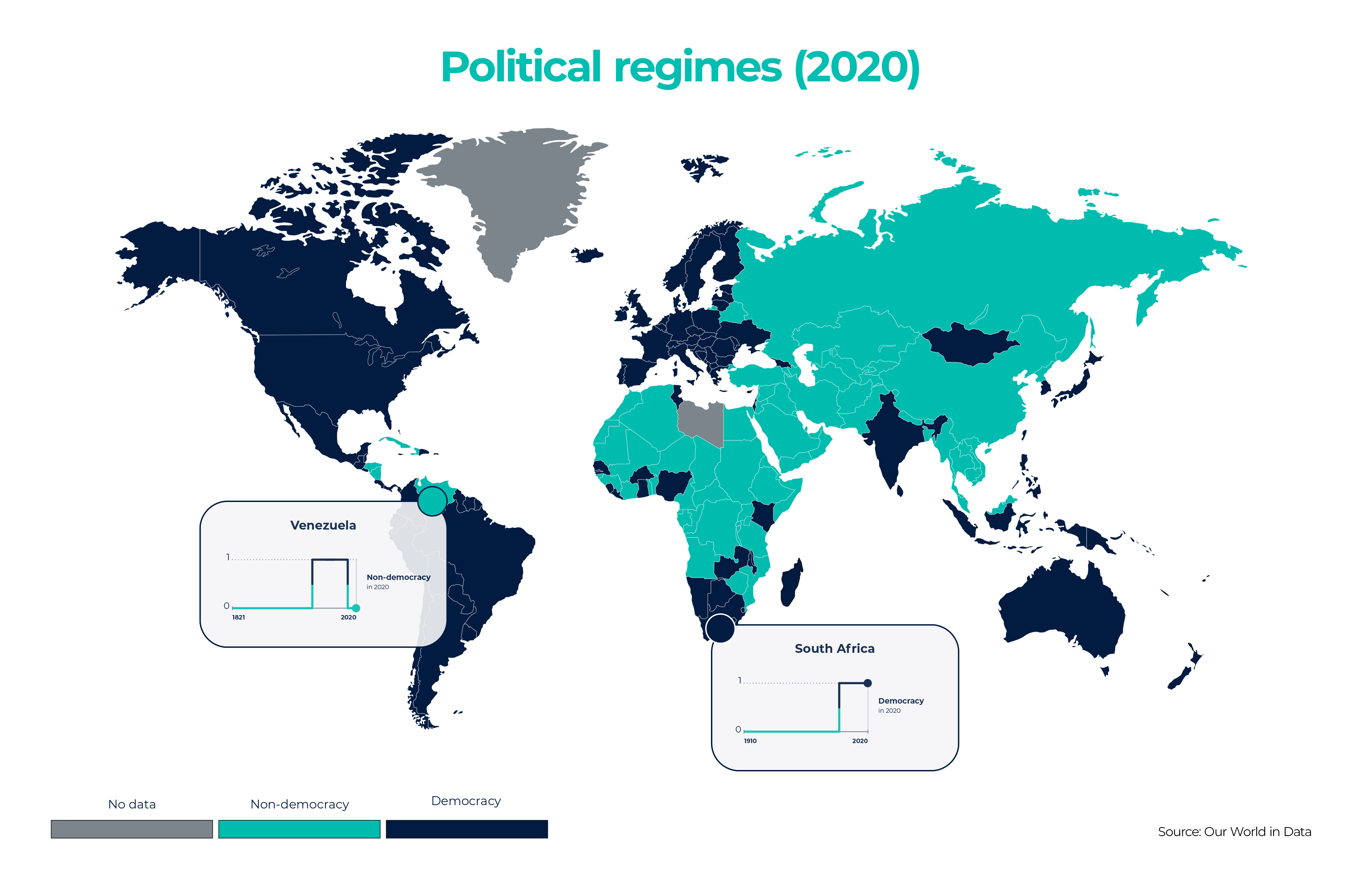

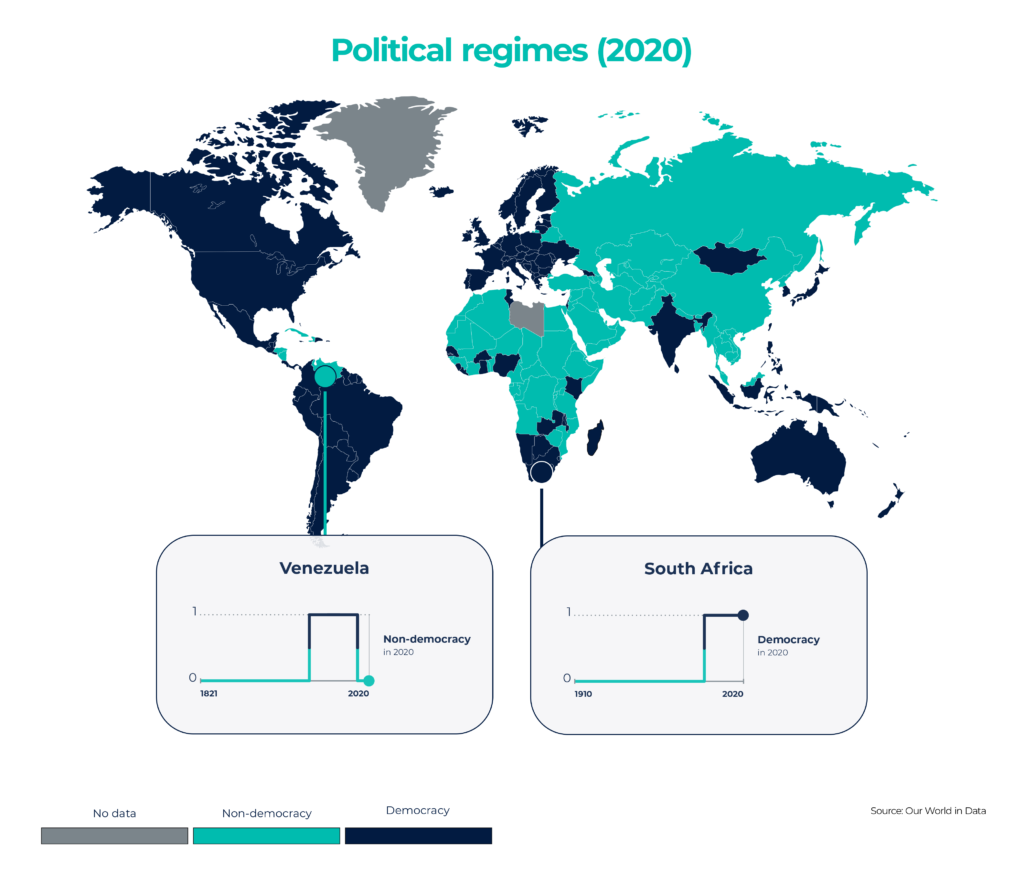

Our World in Data – a project supervised by the University of Oxford – assesses that, based on academic classifications, in 2021 around 60% of the world’s countries were democracies.

Is the world becoming less democratic?

The total number of people who are not granted democratic rights is higher than ever – simply because the world’s population grows faster than democracy spreads. The paths of democracy are complex and discontinuous. Tunisia, for example, became a democratic country in 2012, and has been widely considered to be the only successful democratic model that emerged from the Arab Spring – the wave of pro-democracy protests that took place in the Middle East and North Africa in the 2010s. Yet, now in 2022, the endless power struggle between the country’s president and its parliament has put Tunisia’s democracy under serious pressure.

India is the largest democracy in the world with a population of nearly 1.4 billion people. Given its size, the democratisation of the country in the 1950s brought civil rights to a large share of the world’s population. However, in 2019, the V-Dem Institute – an independent research institute based in Sweden – classified India as an “electoral autocracy”. And now many observers are wondering what the future of democracy in India will be.

“The total number of people who are not granted democratic rights is higher than ever – simply because the world’s population grows faster than democracy spreads.“

And even in countries with long-established democratic institutions, internal forces have begun exploiting the shortcomings of the system, putting democracy itself at stake. In the United States, following Joe Biden’s win in the 2020 presidential election, the then-incumbent Donald Trump promoted numerous false claims asserting that the presidency was stolen from him through rigged voting machines and electoral fraud. His efforts to overturn the 2020 elections culminated in what is now considered the darkest day for democracy in USA: the January 6, 2021 attack on the Capitol.

The suspicion that parties would deny electoral results has also overshadowed the latest elections to take place in 2022: the presidential elections in Brazil and the midterm elections in the United States. So as we look into the future, democracy does not look universal and inevitable. It instead is looking like a fragile conquest to be nurtured and protected.

Why are voter registers so important?

Flawed electoral rolls – with duplicate, outdated or missing names – open up the possibility to manipulate and undermine the trust citizens have in the entire democratic election process. This flaw can not only be used by political parties to cast doubt on the results, but the failure to correctly register voters can also deprive many citizens of their right to vote, impacting the true fairness of the result.

To be a solid democracy it is therefore essential to have solid voter registration processes.

The core of every democracy is trust

Every democratic country’s political system relies on processes that have been built by its own people over decades or even centuries. Yet, at the core of every democracy there is one immutable fact: that the people participate in the decision-making. This can be done directly in what is called a direct democracy or, more commonly, through elections where the people choose representatives to make decisions on their behalf.

Trusted elections are the bedrock of any other democratic process. If citizens do not trust the electoral process, they probably won’t trust anything else coming from the government. Increasingly frequent disputes over the acceptance of election results and claims of voter fraud suggest that trust is at the core of democracy. This means that elections don’t only need to be fair and equal; they also need to be perceived as being trustworthy by the public. It is a tough challenge in which all democracies – from the youngest to the most established – seem now to be involved. So can technology help out?

When biometrics has helped

Building trusted elections is a long-term political and social process that doesn’t happen overnight. But sometimes technology can provide a helping hand.

At the beginning of this century, many countries around the world started to rely on biometrics to compile solid voter registers. This aided governments in overcoming political crises or consolidating fresh democratic institutions, and in other cases it simply made the voting process faster.

One such example comes from Bangladesh – It was 2007, and the parliamentary elections had just been postponed. The decision came after weeks of mounting political violence. An alliance of parties had in fact promised to boycott the elections, with one of the primary reasons being the poor quality of the voter rolls. The list contained over 14 million errors and fake names, which is an extraordinary number given the country had around 80 million voters in total at the time. Pushed by political pressure demanding more trustful elections, the electoral commission decided to use biometrics to compile new and more consistent voter registers. Biometric Voter Registration – often called BVR – is indeed one of the most common uses of biometrics in elections. Biometric data for each eligible voter is captured using biometric registration kits, and stored in the registers together with other biographical and personal information. This makes it easier to detect duplicate names and keep registers clean and consistent.

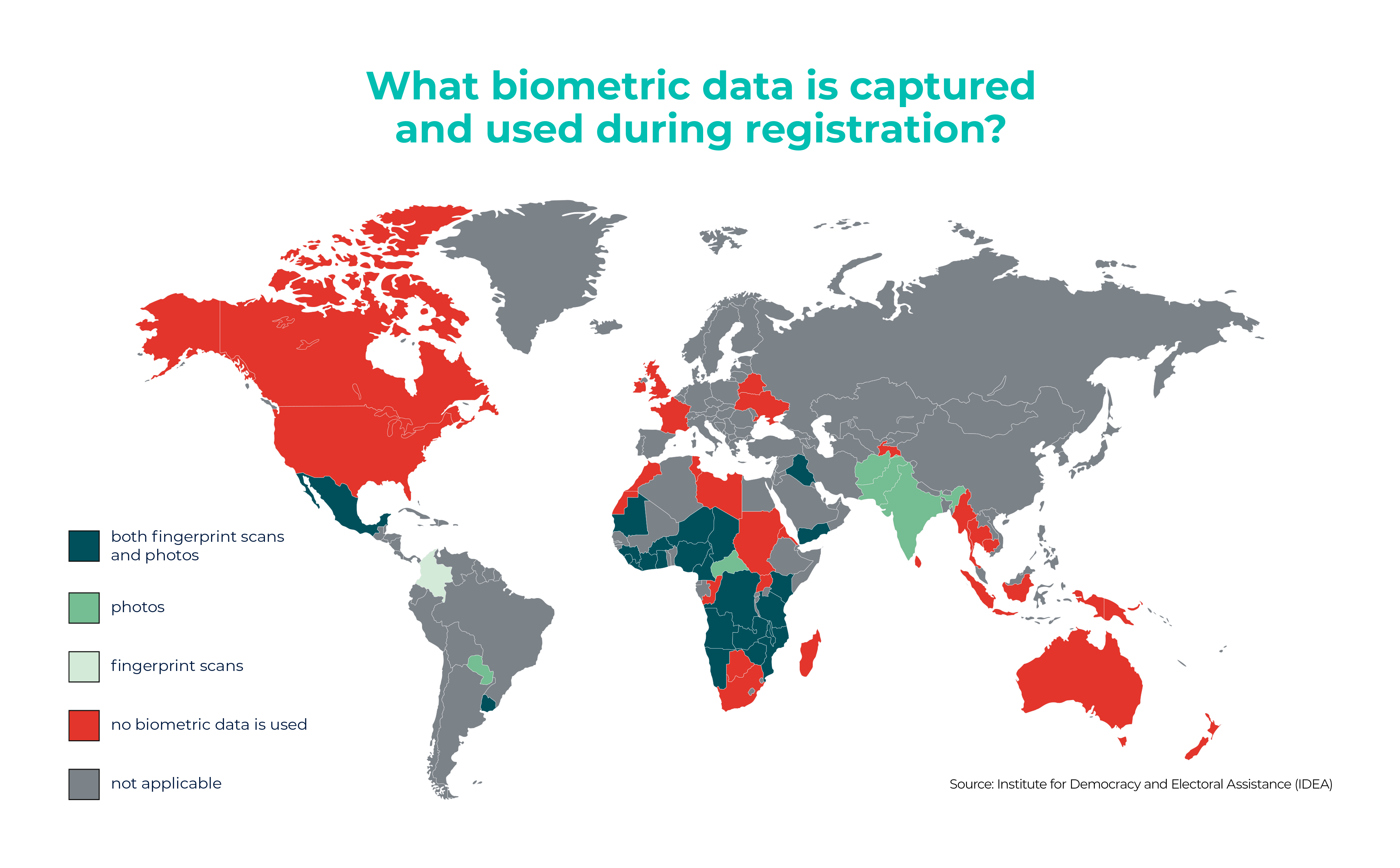

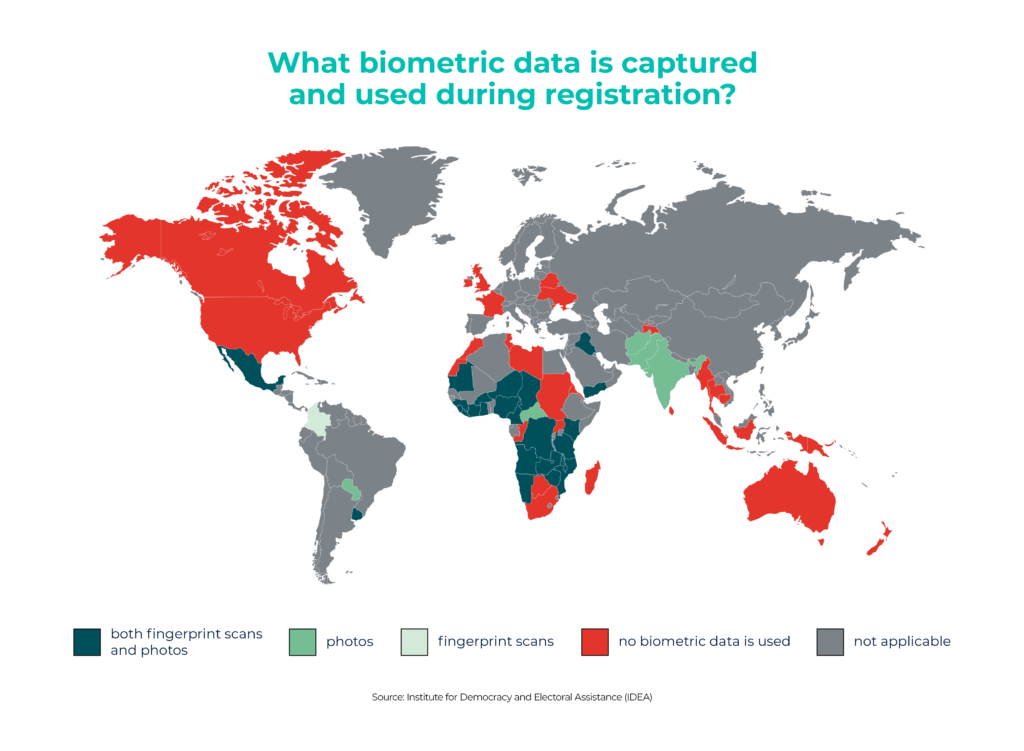

What data is collected through Biometric Voter Registration?

Some countries collect only photos (India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, for example) while others only collect fingerprint scans. Many countries collect both, such as Mexico, Nigeria and Mozambique. Brazil goes even further by also collecting signatures.

“Observers from the International Republican Institute assessed that the Bangladeshi election based on Biometric Voter Registration was the ‘best election in the country’s history’.”

The time was momentous. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) partnered with the Electoral Commission in Bangladesh to secure the necessary resources for the ambitious project. Over 1,000 webcams and fingerprint scanners were distributed across the country, and in just 11 months the commission registered 80.5 million voters. It was a success.

The following year, in December 2008, Bangladesh’s postponed parliamentary election was held. Observers from the International Republican Institute – a non-profit US-based organisation working on the advancement of democracy worldwide – assessed that it was the “best election in the country’s history”.

Biometric voter identification in Ghana led to the highest turnout in history

As seen in Bangladesh, biometric technology can help resolve an acute political crisis by securing voter registration in an accurate and trusted manner. Many other countries are starting to rely on biometrics to compile electoral rolls – especially in countries where citizens do not have reliable identification documents, or population registers are poorly made and not trusted enough to extract voter information.

Biometrics can also be adopted during election day to identify voters at the polling stations, thus avoiding fraud, identity theft and multiple voting. Ghana, for example, decided to use biometrics in its 2020 election in order to both compile voter registers and to identify the voters on the day.

How many countries adopt biometrics in elections?

According to the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), 33% of 177 surveyed countries capture biometric data as part of their voter registration process, while 30% use biometric information to identify voters at polling stations.

Usually, biometric voter identification involves manual verification, such as a poll worker checking a voter’s appearance against a photograph on a voter list. Only 9% of the surveyed countries use an electronic biometric identification system, in which a computer verifies the identity of the voter.

By adopting the latest biometric technology, 17 million eligible Ghanaian voters have been registered – both in urban and remote locations. And all this during a pandemic. “The freshly-compiled voters’ register is arguably the most credible voter register in Ghana’s history,” commented Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, the President of Ghana.

At the polling stations on election day, a fingerprint and facial image verified the voter – acting as proof that a citizen had cast their vote. As an added measure to prevent fraud, printed poll books were also used to identify the voter. Once a verified voter cast their ballot, the electoral officer registered it on both the verification device and the printed poll books, meaning there was zero chance for any citizen to rejoin the queue and vote again.

“The 2020 Presidential Elections in Ghana experienced a turnout rate of 79%, the highest to date.”

The biometric system implemented in Ghana was highly successful – securing the voting process to an internationally accepted standard. “The 2020 Presidential Elections were efficiently and successfully organised; the elections were transparent, credible, fair and met international standards.” – something that all the political parties agreed on. The 2020 elections also experienced a turnout rate of 79%, the highest to date.

Albania is another successful example. In 2021, the country coupled electronic voting and biometrics authentication to help deliver faster and more reliable election results – something that it was complemented on by numerous international observers. The new system also eliminated the issue of multiple voting from patriarchs, securing the democratic principle of one person, one vote. Albania only began holding democratic elections in the 1990s, and decided to adopt biometrics to prove its elections were as solid as possible while qualifying for admittance to the European Union.

Biometric technology can help democracy. But alone, it is not enough.

Since 2009, Bolivia has also been using biometric voter registration. This was an important year for the country: the 2009 presidential and legislative elections were the first to be held under the new constitution which established Bolivia as a plurinational state.

Just before the elections, the opposition parties questioned the accuracy of Bolivia’s voter registry: they argued that the old registry contained many duplicate records, while also excluding many citizens that didn’t have identification documents. For this reason, the electoral commission decided to use biometrics to rebuild the voter registers.

The rise of facial biometrics in e-Government

In digitally advanced countries, biometric population registers can also be used to secure reliable e-Government services for its citizens.

Governments can roll out apps whereby citizens can apply for an ID or renew their driver’s license using their biometric credentials. The same procedures can be applied to visa processing or for obtaining a pension, welfare and health benefits. Find out more about the rise of facial biometrics in e-Government here.

The effort was huge. Over 3,000 registration centres were set up all over Bolivia, from the Andes to the Amazon, and more than 3,500 people were trained to help with the registration. Everything worked quite flawlessly, and thanks to biometrics five million people were enrolled in the new register – many more than expected – in just 75 days. It was a world record in speed for setting up a voter registration.

In the years that followed Bolivia’s creation of its biometric voter registry, international observers such as the US-based Carter Centre highlighted how this biometric register had alleviated mutual distrust and renewed public confidence in the electoral process.

“Bolivia set a world record in speed for setting up a voter registration. Five million people have been enrolled in the new Bolivian register, thanks to biometrics, in just 75 days.”

However, the socio-political environment has always been highly polarised in Bolivia, and since 2019 the country has entered a state of political unrest. In that year, accusations of election fraud led to days of street protests and the resignation of longtime President Evo Morales. The biometric register was not cited among the allegations leading to the cancellation of the election however, and it was still found by the Organisation of American States to be generally reliable.

The path towards democracy and a more equal society is rarely straight and is often unpredictable. Building trusted elections is a complex process: it takes politics, it takes civic action, it takes time – and it may experience setbacks. Even if biometrics can strengthen the credibility and inclusivity of elections, technology alone cannot solve cultural and political issues. It is just one of the many tools countries and people can choose to use to better foster democracy.

AUTHOR

Giovanni Blandino

PHOTOS

Shutterstock

SOURCES

Our world in data

The Expansion of Authoritarian Rule

India’s Democracy Is the World’s Problem

Biometric Technology in Elections

Successful Societies

Ghana’s 2020 National Elections

IPAC COMMUNIQUE

Building a biometric voter registry

Observation Mission Bolivia

Five things to know about BVR